Best Lens for Landscape Photography - Let's Compare Results!

UPDATE: I recently reviewed 7 lenses best suited for landscapes at night! Read it here.

So you’re in the market for a new lens and you know exactly what you’re going to do with it. Your next lens is primarily for landscape photography, but you’re undecided. Should you go as wide as you can go, get a lens that is as sharp as possible, or one with an X-factor you haven’t yet considered? In this comparison, we’re going over the best lenses for landscape photography and why I think these are the great options.

Introduction

First off, who am I to tell you what lens to buy? I’ve been a landscape photographer for close to 15 years now and a professional in the field for a decade. As such, I’ve had both the pleasure and frustration of buying, testing, returning and selling dozens of lenses, ranging from ultra wide-angle Nikkors to super telephoto Canons. I’ve written about gear in my books, on this website and many others like Shotkit, Fstoppers, PetaPixel and Zoom.nl. While I don’t want to come off as a know-it-all, I do want this article to be helpful to anyone asking the most asked question: “which lens should I buy for landscape photography”? Well, I’m not a salesman working at a camera store and don’t keep up with the latest tech or gear. The advice in this article comes from experience. And I do not write about lenses which I don’t recommend, save for 2 exceptions.

Best Ultra-Wide Angle Lens

We’re progressing through this article from wide to telephoto, so let’s start with the best lenses in the sub 20mm focal length category first.

Fish-eye Lens

I’ve tested one diagonal fish-eye lens, with the goal of creating interesting nightscape photography. The difference between diagonal fish-eyes and circular fish-eye lenses is that a circular fish-eye actually has a circular frame, whereas any diagonal fish-eye covers the entire sensor. I’ve found the Samyang 12mm f/2.8 ED AS NCS diagonal fish-eye to be wonderful for the job as there is little chromatic aberration in those images. Pair that with the weird and freaky bending of the horizon when you point it up and you have a tool that can potentially create captivating images.

However, aside from there being a considerable amount of coma (elongated color fringed stars, particularly in the corners), I found the perspective really quite boring after 2 nights already. The Milky Way is very small in the frame. And if your goal is to photograph the Milky Way, then I recommend zooming in more. But we’ll get to that. I do like the effect when pointing up from a huge tree.

Shot with Samyang’s 12mm Fish-Eye on Nikon. I’ve de-saturated the stars a lot to make the amount of coma not too displeasing.

Best Rectilinear Ultra-Wide Lenses

Man, I’ve tested a bunch over the years. On all different platforms. Rectilinear means that they do not distort the way fish-eyes do. On the Canon APS-C, the platform I started out with, I loved the Canon EF-S 10-22mm F/3.5-4.5 USM. It’s great for any subject within landscape photography when you’re on a cropped Canon camera. It might not be as sharp or as fast as other lenses, but due to its relatively low price point, the 10-22mm is a perfect candidate for landscape photography. You know, sharpness wide-open isn’t that important to landscape photographers anyway. We rarely shoot at f/2.8, save for under starry skies to gather as much light as possible.

Shot in 2012 using my Canon 550D (EOS T2i) using the EF-S 10-22mm F/3.5-4.5 USM.

Samyang has a couple of ultra-wide lenses on offer. I’m not affiliated with them, but I liked their price point in a time when I didn’t have too much cash to spare as a poor student. Especially considering how high the quality is. Their original manual focus 14mm F/2.8 was my go-to lens for many years when I switched to Nikon. The beauty of these third party lenses is that their optical qualities are the same regardless of the lens mount. But be careful that in most cases, Sony E-mount lenses are often a little different. I can also vouch for the Samyang 14mm F/2.8 AF Sony FE, which does offer the same sharpness and auto-focus to boot. Great lens.

Strong northern lights in the Netherlands shot with the Samyang 14mm F/2.8. The older manual focus version. It has a slight mustache distortion that’s visible only in straight horizons, but easily corrected in post.

Speaking of third-party lenses, at the time of writing I’m using the Sigma 14-24mm F/2.8 DG HSM Art for Nikon. There’s a reason you hear about Sigma Art lenses: they’re pretty much flawless. Really, they are that good. But that is not the reason I went with this wide-angle zoom. I traded it in for the aging but still good Nikon AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm F/2.8G ED. The reason is that I can focus a little closer than I could with the Sigma than I could with the Nikon one. And at 14mm, a difference of 2 centimeters means a lot! Check out the Nikon 14-24 vs. Sigma 14-24 comparison and see for yourself.

Shot with the Nikon 14-24mm.

Shot with the Sigma 14-24mm.

A few years ago, I also photographed with the Tamron SP 15-30mm F/2.8 Di VC USD for a while. It’s hard for me to properly review that one, because my brand-spanking new copy was decentered when I got it. That means that one half of the frame would be in focus, while the other was not. The trouble is, is that I discovered it when I returned from my photo tour to Iceland and all my images of the northern lights were just a bit unsharp on either the right or the left side, depending on which star I focused manually. Luckily, my focus stacks were successful so it wasn’t a total loss. But I got Nikon’s 14-24mm instead after that 2016 trip. Quality control was apparently an issue with that 15-30mm.

Shot with the Tamron SP 15-30mm F/2.8 Di VC USD - One image that I salvaged with this de-centered copy because I focus stacked this image meticulously.

Best Wide Angle Lenses

I had a brief encounter with the Canon EF 20mm f/2.8 USM, but did not like the sub-par performance. Instead I’d go for the Samyang 24mm F/1.4 ED AS IF UMC. Samyang’s 24mm is arguably the best lens for nightscape photography. Period. It does not have ANY optical defects or aberration wide-open. At f/1.4! That means shorter exposure times, and a much brighter Milky Way. And I believe 24mm is the sweet spot for photographing the galactic center anyway, because unlike wider lenses, it shows more detail and less stars (which look like noise at wide focal lengths).

Shot with the Samyang 24mm F/1.4 ED AS IF UMC

As we move on along the zoom range, we’ve arrived at Sigma’s 35mm F/1.4 Art DG HSM: the sharpest wide-angle lens I’ve ever used. And it’s sharp from wide open onward. Combine that with the fact that it also does not have any coma or other aberrations when used at f/1.4, and you have another winner for nightscapes and close-ups of the Milky Way’s galactic center. It’s a relatively big and heavy lens, and I don’t have much creative use for the 35mm focal range. That’s why I don’t use it anymore. But if 35mm is your thing, this is the top lens you should consider.

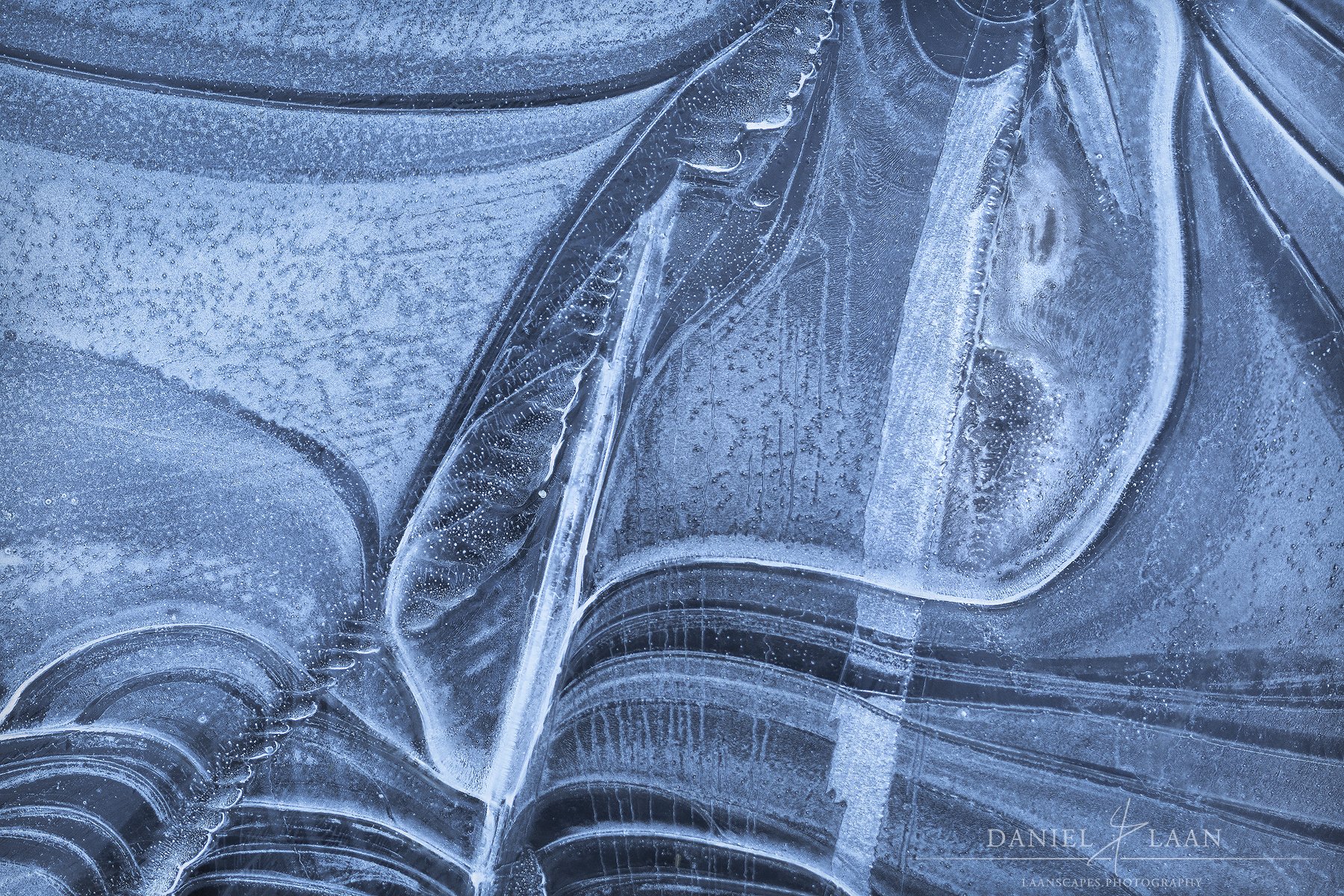

I’m sorry that I don’t have a shot of the Milky Way core for you at 35mm. And full disclosure, this image was a salvage from 2015 when I still had the Sigma 35mm F/1.4 ART DG HSM. Somehow I forgot to bring my tripod that morning. So I shot this handheld in twilight, wide open at f/1.4. I needed to bump the ISO to 800 to get a workable shutter speed and not get movement due to the quite heavy lens and the awkward angle. While it was shot straight down, this is a crop of a 2 shot handheld focus stack. Neither image was in completely in focus. This image has capture sharpening, unsharp mask, high pass sharpening and output sharpening, but I never told this was a lab test of these lenses. This is a real-world review of all the best lenses I’ve ever owned. And I quite like how this turned out despite the fact that I messed up in the field. It’s called “Ice Scream”. Can you see why? Like the face in the ice, I liked to bang my head against the wall after forgetting my tripod.

Best Normal Lens for Landscape Photography

Normal lenses are called that way because they translate human vision quite well. 50mm lenses on full-frame cameras show a field of view that looks like what we see with our eyes. On cropped (APS-C) cameras, the field of view is magnified, which leads to an apparent focal length of about 85mm. In the range from 50 to 135mm though, you will find the sharpest lenses in the world. You can’t go wrong with basically any lens in this focal range, but there is a cream of the crop. My current nifty fifty is the Nikon Z 50mm F/1.8 S-line. What I said about 35mm lenses is true for this focal length too: I don’t have a lot of creative use for it. But whenever I do find an awkward in-between scene that is too wide for my 70-200 or where the subject is too tiny on the 14-24, I grab this seriously light lens. And it is a joy to work with. While it does exhibit some chromatic aberration at f/1.8, I don’t shoot at this aperture anyway. In landscape photography, you’re better off shooting at apertures of f/7.1 to f/14. This lens is insanely sharp and I find myself using it more often because of it, while procrastinating on more creative shots using more specialized lenses on either end of the focal range.

Originally, this was a vertical shot of the Matterhorn with a few foreground details. But I figured that this particular foreground didn’t add anything to these insane skies and already iconic mountain. I ended up cropping the image. This is a crop of about the top half, shot on the 45.7 MP Nikon Z7. Due to the bizarre sharpness of the Nikkor Z 50mm f/1.8 S-Line, cropping is never a problem. I shot this at f/9 and ISO 64. The sharpest aperture of this lens is slightly below that, but I closed it down a bit to add depth-of-field for the foreground that I ended up cropping out.

Best Short Telephoto Lens for Landscape Photography

Now this is very often dubbed the range for portrait photography, due to the flattering perspective 85-105mm lenses have on the human face. As I’m an introverted landscape photographer, it probably wouldn’t come as a surprise that I dislike photographing people. But I do use the same lenses as wedding- and portrait photographers. I’ve tested three or four 85mm lenses, all by Nikon. And they were all great once stopped down to landscape photography apertures. There was one exception. The Nikon AF-S Nikkor 85mm F/1.8G is sharp from about f/2.8, even though I did not usually shoot at that aperture. Past tense, yeah. Now I use a 70-200 telephoto zoom that covers that range too. And the Nikon AF-S 70-200mm F/4G ED VR (no link) is only a hair softer than the 85mm f/1.8G.

One of my all-time favorites: “The Waking Forest”, shot with a ‘portrait’ lens: the Nikon AF-S Nikkor 85mm F/1.8G.

The 70-200 f/4 is my most used lens to date. It’s light, versatile and sharp wide-open. My go-to lens for forest photography and distant mountains with a 1.7x teleconverter.

Shot with the Nikon AF-S 70-200mm F/4G ED VR without teleconverter. Note that I almost never not focus stack.

Shot with the Nikon AF-S 70-200mm F/4G ED VR with 1.7x teleconverter for a 340mm equivalent.

Best Super Telephoto Lens for Landscape Photography

We’ve come at the end of the focal / zoom range of photography. This realm is dominated by both zoom lenses that aren’t as sharp as you might hope and prime lenses that have similar price tags of second hand cars. In that regard, it is a tough area to find a lens that fits the bill. But why would you even want to consider such a long lens in the first place if your bread and butter is landscape photography? Well, a telephoto with a longest focal length that exceeds 200mm is the best for landscape photography. I’ll tell you why in a second. Here are my choices:

Nikon Z: Nikon Z 100-400mm F/4.5-5.6 VR S-line (or the above lenses with the appropriate mount converter, which breaks accurate and fast auto focus)

Nikon F: Sigma 150-600mm F/5-6.3 DG OS HSM Contemporary Nikon OR Nikon AF-S 70-200mm F/4G ED VR with additional 1.4x or 1.7x TC.

Shot with the Sigma 150-600mm F/5-6.3 DG OS HSM Sport. The Contemporary version is slightly lighter and slightly softer.

Why Super Telephoto Zooms are my preferred lenses for Landscapes

Where do I start? I would argue that, the longer the focal length, the more deliberate your compositions will be. That not only leads to more personalized crops of the areas that grab your eye, but will gradually force you to be more considerate with photography as well. For a number of reasons. The creative aspect of super telephoto lenses forces you to consider both distant subjects more carefully and close ones more intently. Me and a couple of my landscape photography friends and colleagues love intimate landscape photography for those reasons. We could stand next to each other in the same location and end up with totally different results.

Shot with Canon EF 100-400mm II F/4.5-5.6 L IS USM (on a Nikon Z7 using a mount adapter.)

Check out Martin Kemper, Isabella Tabacchi, Kai Hornung, Ellen Borggreve and Inge Bovens. When we’re shooting together, we’re practically in the same spot. And yet, none of our images look alike. Sure, Kai and I sometimes approach an image in a similar way in post-processing and Martin and I love those misty mountains, but we all wait for different things to happen in the landscape. And the wider you shoot, the longer you have to wait for things to actually have an impact on your work. Consider dappled light on a mountain range. As a viewer, we’ll see alternating shadow and light on a distant mountain range, but when we screw half a meter of glass and metal on our cameras, a 30 second wait can make or break the shot. Clouds are constantly moving, building and dissipating. And those 400mm focal ranges really pronounce the speed at which the landscape evolves. Contrary to popular belief, the landscape isn’t static at all. Timing your image is as important as it is in any other genre of photography and super telephoto lenses hint at your proficiency at it.

They also force us to be very careful from a technical point of view. A long lens has a lot of surface area and the whole tripod setup becomes top-heavy. Even the slightest breeze can ruin an otherwise perfectly sharp image. So apart from the necessary precautions you can take to minimize movement of your setup, you’ll have to time the shot in a lull of the wind too.

Shot with the Nikon AF-S 70-200mm F/4G ED VR with 1.7x teleconverter for a 340mm equivalent. I really had to block the lens using my body and shoot with all the techniques there are to get a result this sharp. But sure enough: 30 seconds later and this cloud moved out of the frame.

Checklist for Getting any New Lens

If you’re buying a new lens, then please consider the following tips I have. I don’t want you to bust the bank just because you got it in your head that you somehow need new glass:

Does the lens you have in mind offer considerable creative advantage over what you have now? Personally, I don’t mind the gap between 24mm and 70mm. When on tour, I do not bring a lens in this focal range, except for the lightest of the light lenses: a nifty fifty.

Is there something you could change in your current workflow that will lead to images that you are happy with? Sharper images can be had with different techniques. Use a sturdy tripod, mirror lock-up or a 2 second self-timer and shoot at f/7.1 to f/11 instead of f/22 or f/4.

Could you use a lens you currently own differently? Macro lenses are very sharp glass due to their focal length and are perfect for landscape photography as well, often out-performing telephoto zooms by some margin.

Lastly, is there any left-over glass in the cupboard that you could sell? Can lenses you do not currently use as often as you once thought help to buy the best lens for landscape photography?

If you are in the market for a new lens, please consider buying one using the links provided in this article. Amazon will then give me a small commission that will help me maintain this website and write more articles like these. I’d like for my website to offer a bit more than “here are my pictures”. 😊

Thanks for reading and I hope this was useful to you.

- Daniel